In the business magazine Bloomberg BusinessWeek, a consultant at Bain & Company, a large Boston consulting firm, talks about the big trend in the business world right now: “Diversity is the new digital number.” Diversity is the new digital number. The consultant believes Bain, which has earned billions from digital switching advice, now sees diversity as the next main source of income. That the advisor himself is white might say himself.

Anti-racism has broadened and increased in the past year. Even the business community in the United States is now making amazing attempts to deal with the racism they seem to have just discovered. It is a step forward in anti-racism that it engages more people than ever before, but it also risks downplaying the importance of the debate about racism.

In The Guardian, young author Yaa Gyaasi says anti-racism writers have “turned into self-help tools” for whites.

In the United States, we see exactly that The white middle class who enthusiastically took part in the demonstrations after the death of George Floyd last year as they settled in neighborhoods with the most dispersed schools in the United States.

In liberal strongholds like New York and Washington, white families with children are paying millions to live in school districts where only children have white classmates. In affluent New York neighborhoods, the “Vigil Against Racism” is organized, where guests get a chance to step back from their stressful jobs by sitting in a circle and pondering away from their white privileges. Certainly a therapeutic experience, but racism will probably need to be combated with some concrete measures.

Maybe that’s why I went back to WEB Du Boi literature last year. In any case, it is hard to imagine an author who would be a better counterweight to the banal statement of a Bain consultant.

Abraham Lincoln announced the release of all slaves, effective January 1, 1863.

Photo: Alamy

Thankfully, that didn’t happen There have been a lot of good books to read about Du Bois. No fewer than eleven new books about him have been published in recent years, while many of his classics have appeared in new editions with introduction and articles with pioneering contemporary voices against racism.

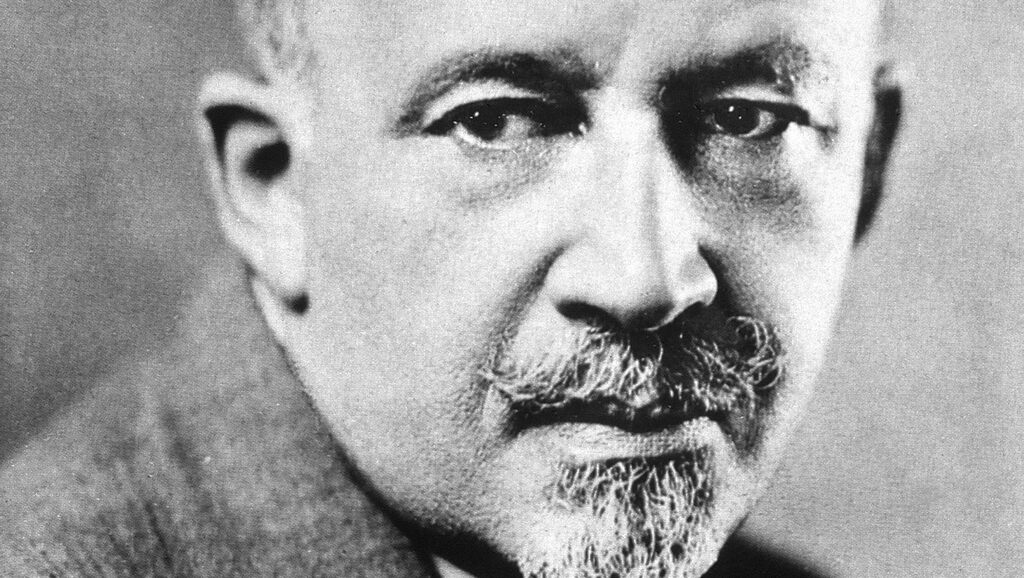

WEB Du Bois was a writer, historian, sociologist, and public thinker who became a pioneer in research on racism in the United States at the turn of the last century. He has published more than thirty books and hundreds of articles, poems and plays.

Du Bois was the first black sociologist to publish scientifically and the first black American to hold a Ph.D. from Harvard University. For 80 years professionally, he published his books that pioneered the modern anti-racism vocabulary. It is impossible to understand the contemporary United States without reading it.

Du Bois was born in 1868 In western Massachusetts, three years after the end of the Civil War. He belonged to the first generation of blacks to rise after slavery. He became a sociologist because he was convinced that statistics and science were the most effective tools for exposing and combating racism. Methodically and patiently, he mapped the mathematics of racism, making it clearer than any other researcher.

Racism was also present at a time when the infant stops breathing in your arms

When he moved to Georgia in the American South to study, he saw with his own eyes the brutality of apartheid. In a memorable article, he wrote about a shop window where a store sold a severed hand from a recently executed black man – a souvenir to show who decides in the South.

During his years in Georgia, his eldest son, Burghart, passed away, barely a year old. White doctors in the state didn’t want to treat him. It was a personal and political tragedy. The son became a victim of racism in Georgia. Du Bois convinced that it was not possible to measure racism not only in numbers and graphs, but also in personal life stories, in our most intimate moments. Racism was also present at a time when the infant stops breathing in your arms.

In the new introduction to Du Bois classic Black Spirits by Abram Kennedy shows how the years in the Southern Du Bois and in the long run also changed American literary history. Dubois had said at the outset that racism could only be treated with “more knowledge and science”. But years later in Georgia, he wrote instead that it was no longer enough to be “a sane and neutral world, while blacks are executed, killed and starved.”

He saw the academic distance of sociology insufficient to elicit real commitment. Instead, he wanted to write with the emotional record of fiction, portraits of poetry and lament of activity.

Thus he developed a hybrid literary form, which allowed him to be a scholar and civil rights activist. In the classic collections of essays such as “Black Spirits,” “Dark Waters,” and “Dusk of Dawn,” he combined the personal, the scholarly, the intimate, and the universal.

When he was appointed an honorary doctor at Humboldt University in Berlin in the fall of his life, he was precisely motivated by the fact that he had achieved “a unique combination of scientific research and political activism”.

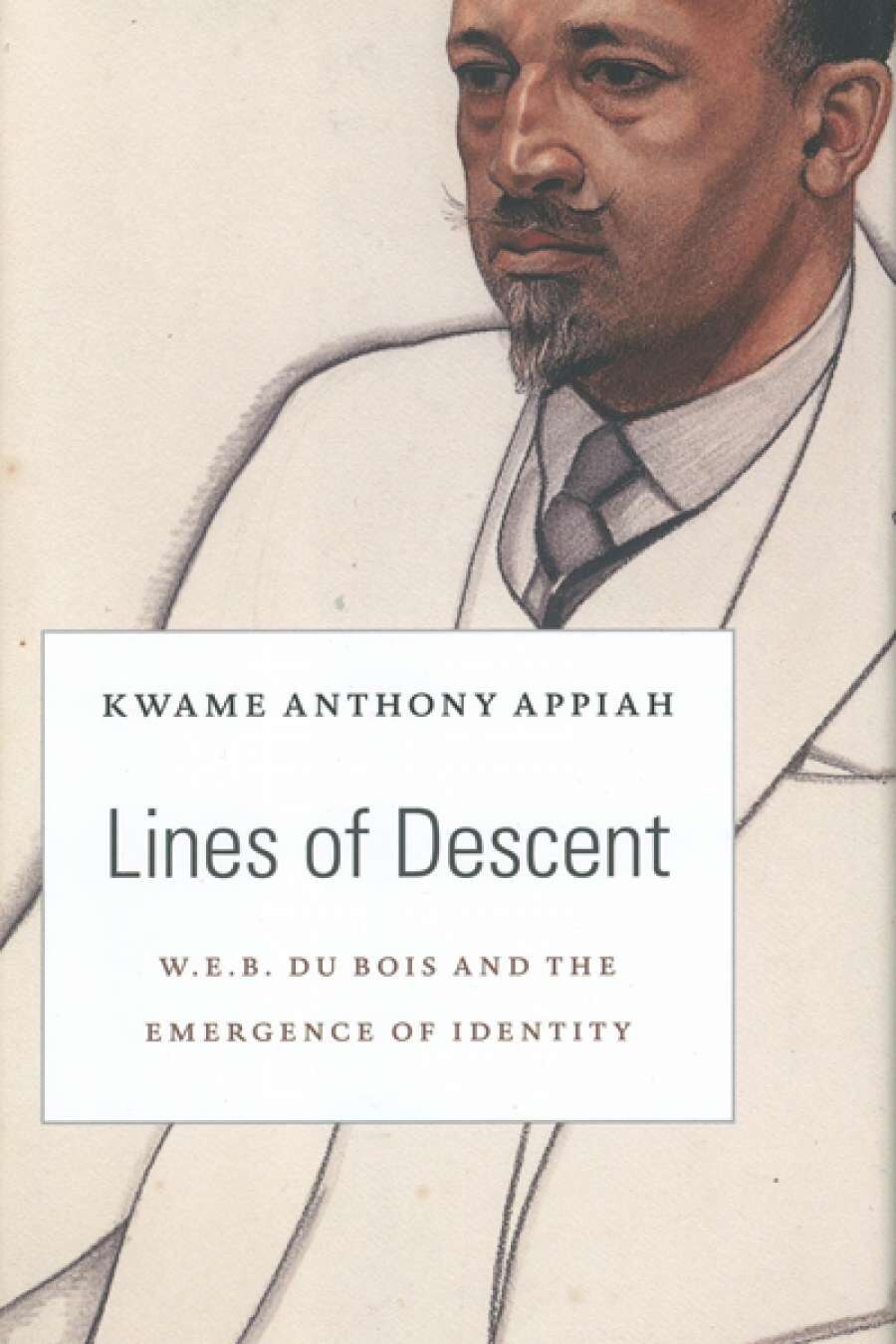

Of all the new books on Du Bois, Martin Gellin’s favorite “lineage lines” is Kwame Anthony Appiah.

New books If Du Bois accurately reflects this breadth of thought. In “Visualizing Black America,” by Princeton Architectural Press, Du Boi’s groundbreaking drawings were compiled, as he pioneered a new design language to provide statistics on racism and discrimination. A new biography of Du Bois, written by Elvira Basevich and Reiland Rabaka, in turn affirms feminism and his struggle for women’s suffrage. When he founded NAACP, which to this day remains the most important black civil rights organization, he was inspired by the National Association of Women of Color, founded by Ida B. Wells and Harriet Tubman fifteen years ago.

In the mega-harvest of books about Du Bois, my favorite is Kwame Anthony Appiah’s “Genealogy: WEB Du Bois and the Emergence of Identity”. While many of Dubois’s biographies attempt to cram him into an ideological or disciplinary section, his father instead espouses what he calls “disciplinary schizophrenia” by Dubois. He writes that Du Bois “invented a new way of writing about racism in the United States”, combining the authority of a scholarly scholar with the explosive emotional power of personal testimony. It is a well-known prose style for many of the great black American writers who followed in Du Bois’s footsteps – from Ellison and Baldwin to Morrison and Coates.

American racists never made a distinction between identity politics and economic redistribution policies. It would therefore be unreasonable for anti-racists to divide such a split.

Appiah, himself one of the leading philosophers of our time, believes that Du Bois invented a new way of writing about black identity. Today, identity politics is a term used almost exclusively by its critics. It’s often described as a distraction, a bunch of mundane babysitters and Twitter discussions about Oscar nominations. But Du Bois showed that identity politics arose to speak of extrajudicial executions, mass killings, colonialism and torture. It is about black men in the south who were killed because they tried to vote. Thirteen-year-olds were killed by police bullets a hundred years later.

Yet we constantly see how the term “identity politics” is being used to attack modern anti-racism.

I am Scriver Financial Times Usually visionary Simon Cooper: “Forget the politics of identity – the economy is now the most important thing.” But it is a false contradiction, based on a misunderstanding that there will be a trench between identity politics and some kind of “serious” realpolitik, which relates to economics, infrastructure, and material conditions.

American racists never made a distinction between identity politics and economic redistribution policies. They do not distinguish between the daily harassment and the structural racism expressed in housing policy, criminal policy, and tax policy. It would therefore be unreasonable for anti-racists to divide such a split.

Du Boy’s literature reminds us that the entire United States remains a mystery, an impenetrable maze of contradictions, for anyone who refuses to see how racism has left its mark on nearly all critical political changes since the Civil War. The patterns he described repeat over and over again.

Once a certain amount Blacks gain access to a public institution in the United States and whites begin to flee or cause violent uprisings and sabotage. The conflicts today look different than they were in Du Puy’s time, but they are the same racism. In New York, white parents are moving their young children more eagerly than ever to school districts with the lowest percentage of black students. In Washington, Congress is attacking in an attempt to save a racist president who lost the election by 7 million votes. In Georgia, white politicians with increasingly sophisticated gimmicks are trying to stop blacks from voting. As the electorate becomes less white, attacks mount on the voting system itself.

There is an echo of Du Bouy’s warnings that democracy cannot survive if the United States does not succeed in taming racism as a political force.

“Unapologetic writer. Bacon enthusiast. Introvert. Evil troublemaker. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

A 50-year-old karate man kicked a bear in the face

Sunak: Migrant flights to Rwanda this summer already | the world

A German arrested on suspicion of espionage – an assistant to the main candidate in the European Union elections