Imagine a triangle: in a corner of the Western world’s colonial conscience and genocide that claimed nearly a million lives; In the next corner is what is described as an increasingly repressive dictatorship; In the third – the rule of law.

In the middle you have a 44-year-old father of two who lives in Gothenburg, has been held captive for ten months and risks being extradited to Rwanda, despite his denials, to stand trial for genocide.

This case is one of the few in Sweden. The Supreme Court decided to extradite a Rwandan suspected of genocide in 2009, but the suspect left Sweden before the extradition could be carried out. Three Rwandans were convicted of genocide in Sweden and are serving life sentences in Swedish prisons, but these cases were adjudicated in Swedish courts, not in Rwanda.

Thomas Bodstrom and colleague Hannah Larson Ramby.

Photo: Jonas Lindqvist

Thomas Bodstrom is A lawyer for the 44-year-old detainees, he has long been involved in cases related to the legal consequences of the Rwandan genocide. Bodstrom previously served as an assistant prosecutor in genocide trials, but now he will defend a man accused of having had a role, as he is often called in these cases, an unofficial leader in a genocide event.

– This is an extradition case, so it’s not really about whether he’s guilty or not, but whether he’ll be able to get a fair trial in Rwanda, says Thomas Bodstrom.

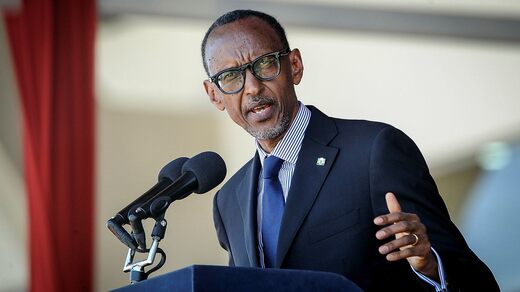

Paul Kagame has been President of Rwanda for 21 years. According to Bodstrom, the Kagami regime uses genocide to prosecute its opponents.

– I think there is a general strategy from Rwanda to continue the genocide trials. It’s been 27 years, but I think it’s important in principle to take into account the genocide. Thomas Bodstrom always says that they say you should go forward, but in reality you do the opposite.

Paul Kagame has been President of Rwanda for 21 years

Photo: John Muchucha/AP

Swedish goal colorful The International Politics. In Norway, the government decided last year to reject a request to extradite a man to Rwanda, stating that trials in the country could not be considered to live up to the Norwegian level of legal certainty. In the UK, the same has been proven in court.

The reason is because it was a horrific genocide, and it is very important that you remember it and it is important that you do not appear as a genocide denier because you are now claiming that Rwanda is a dictatorship. You should be able to keep two thoughts in your head at the same time, says Thomas Bodstrom.

The client represented by Thomas Bodstrom and his colleague Hana Larson Rambe is a Burundian, but originally from Rwanda and belongs to the Hutu ethnic group. 15 years ago, he lived in Gothenburg, where he met his wife, a Burundian woman who, according to her statement, belongs to the Tutsi ethnic group. Together they have two young children.

The 44-year-old is undergoing two parallel legal procedures in Sweden. The first relates to the extradition issue, but if Rwanda’s extradition request is denied, it is not certain that he will be allowed to leave prison in Gothenburg. A Swedish preliminary investigation into the same crime is also underway and the 44-year-old can be remanded as a suspect in the framework of this investigation.

Article that The basis of an extradition case is shrouded in secrecy, but according to Bodstrom, the Rwandan investigation consists almost exclusively of written oral testimonies. It is a fact that according to Thomas Bodstrom and Hannah Larsson Rambee by itself means that the material must be questioned. Swedish lawyers refer to reports from Rwanda where the same witnesses appear to appear with the same accounts in different court cases, with the only difference being that they refer to different perpetrators.

“Sweden has to depend entirely on a dictatorship. We don’t have a chance to check this for ourselves,” says Thomas Bodstrom.

Photo: Jonas Lindqvist

Thomas Bodstrom claims that the rulers of Rwanda are looking for his client because he is active in opposition to the regime:

He was in contact with people who are the regime’s biggest critics.

Martin Whitwin A Dutch lawyer who has worked for a long time on cases related to genocide trials in African countries, including immediately in Rwanda. In 2015, he wrote a report to the Rwandan Attorney General in which he specifically outlined the shortcomings he believed to exist with regard to defense lawyers in Rwanda.

Although Witteveen wrote in the report that he believed the Rwandan legal system would be able to undo the genocide, but only on the condition that the quality of defense lawyers’ work be raised to an international level.

And the lack of competence among Rwandan defense lawyers is not the only criticism that Martin Witvin has in the Rwandan trials. He witnessed several genocide trials in court in Arusha, Tanzania, and told DN that there is a consensus in Rwanda for the story that is allowed to be told when talking about the 1994 genocide. In this account there is no way of seeing Hutus as anything other than the perpetrators.

On the surface, the Rwandan legal system appears to be working well. Defendants have lawyers, judges are professionals, and prisons aren’t that bad. But everyone knows that even if the defense were allowed to call its witnesses, no one would believe them. It is a deeper issue that has to do with the mental state of the legal system. Everyone knows that the Hutu will be judged. I’ve seen examples of judges who have made very peculiar assessments of the evidentiary value of statements that can help defendants, he says.

But Martin and Stephens and Thomas Bodstrom’s position is not the only possible one. Innocent Musonera is a Rwandan defense attorney with a PhD in Law from Uppsala University, where he compares African lawsuits to European and American cases. He told DN that although it could be argued that Rwanda’s democracy is not as developed as Swedish democracy, it still seems implausible that genocide trials should not take place:

Genocide happened, it’s not fiction, it’s reality. There are many victims demanding justice. Most of the perpetrators are contractors of justice and live in different countries, such as Sweden. Rwanda must be able to bring the perpetrators to justice.

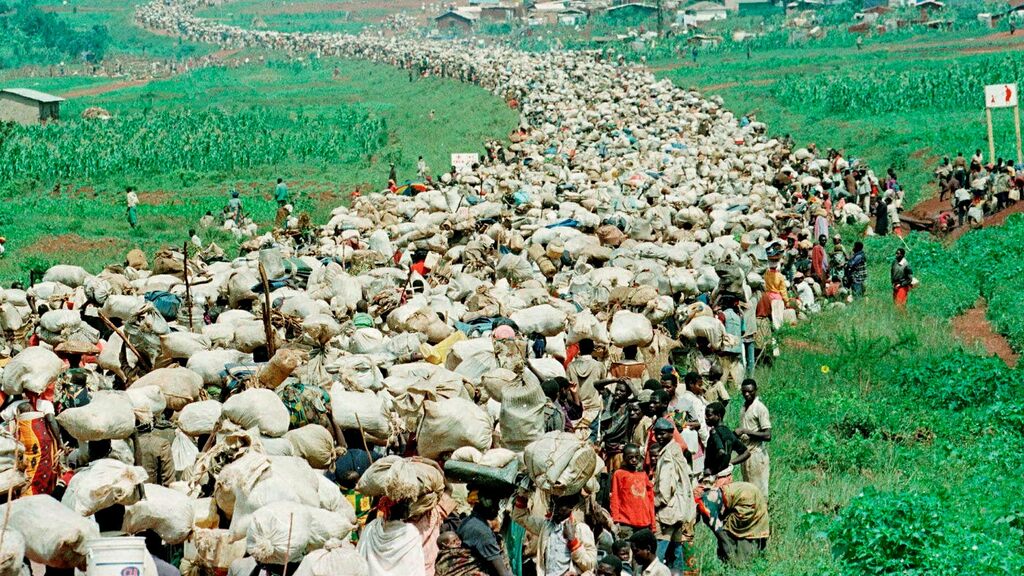

Volunteers work to find the remains of a mass grave from the 1994 genocide. The organization working on the site and local authorities believe there may be around 5,000 bodies in the cemetery in Gatsipo, eastern Rwanda.

Photo: TT

But can Rwanda guarantee a legally safe procedure?

Rwanda may not be on the same level as Sweden, if we are to compare. But should genocide cases be prosecuted? The answer is yes. Because if you look at the cases that were transferred to Rwanda from other countries, the procedures were fair.

But Swedish lawyers The main objection to extradition to Rwanda is actually more general than this:

The evidence depends entirely on Rwanda being a country governed by the rule of law, which it is not. This means that Sweden must depend entirely on the dictatorship. We don’t have a chance to review this ourselves, says Thomas Bodstrom.

The Prosecutor has investigated the Rwandan request for extradition, which finds that he sees no obstacle to extradition before the Supreme Court. If HD still opposes extradition, this will be ruled out, but if the court finds no obstacles, the government has the last word and can stop the extradition.

The prosecutor’s opinion is also covered in secrecy, but Boudel Basman, who took the case to the attorney general, agrees to speak about it in general terms.

– You go to extradition and we’re not the one doing the preliminary investigation. The preliminary investigation is underway in another country, in this case Rwanda, after which we will not test whether he is guilty, but whether there are obstacles to his extradition, she says.

Britain and Norway have stopped extraditing criminals to Rwanda, do you feel confident that this man will have a fair trial in Rwanda?

– We know those decisions. On the one hand, we share general information about the legal system in the other country, and on the other hand, we look at the case law in other countries. This includes what you said, but that also includes the others that were delivered. There are also UN resolutions that have considered allegations of torture in an extradition case, says Boudel Basman who follows:

– In July the Netherlands delivered, so it was even later than this Norwegian, so both happened.

– We came to the conclusion that there is no general drawback, but you have to try it in individual cases, says Bodel Besman.

A memorial to the victims of the genocide in Kigali, Rwanda.

Photo: TT

But were you able to verify the information that would then form the basis of the delivery in this individual case?

– Yes, that depends on what you mean. Now I must only say that we have tried this case in light of all the public information and case law in other countries in the near future.

Thomas Bodstrom means that Swedish prosecutors, through earlier decisions, had placed themselves in a corner where, he said, in their eagerness to help Rwanda deal with the genocide, they had become vassals of a dictator.

– We have sentenced three people to life imprisonment and relied on evidence from Rwanda. So they are sitting in fox scissors. They move on from being heroes helping victims of genocide, he says and continues:

– Therefore, it is not only bad that a father of two children is in prison for ten months, but other fathers of young children are in prison. Then it was no longer about the Rwandan genocide but about the innocent people in prison.

“Unapologetic writer. Bacon enthusiast. Introvert. Evil troublemaker. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

More than 100 Republicans rule: Trump is unfit | World

Summer in P1 with Margrethe Vestager

Huge asteroid approaching Earth | World