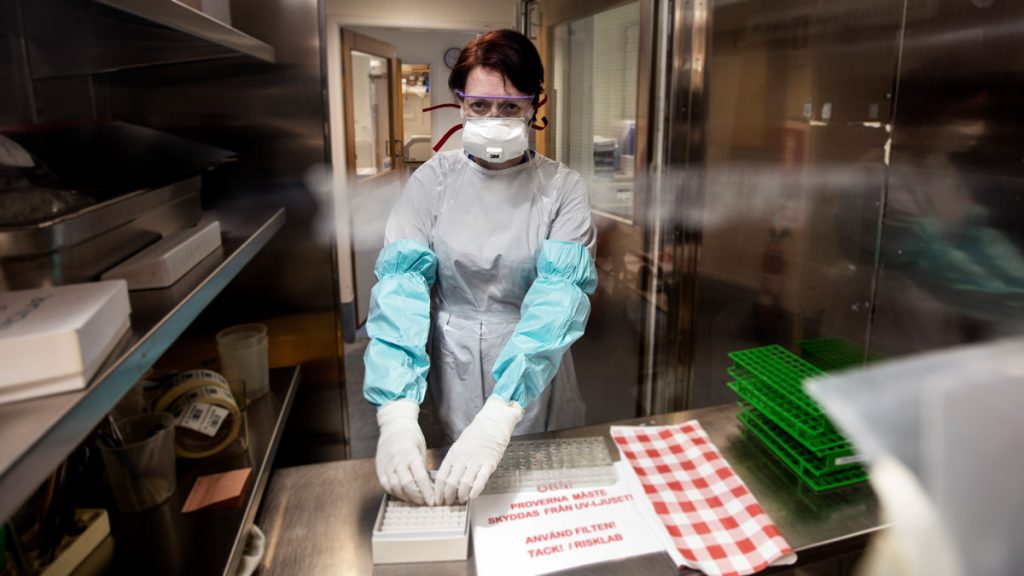

Christina Nystrom, a medical microbiologist at the Salgarneska Academy, has been in constant close contact with the Coronavirus. Since April 2020, she has been entering her lab regularly through the airlock, complete with a protective coat, a plastic apron, plastic sleeves and double gloves. Respiratory protection and goggles are the obvious equipment.

In a lab bench with air extraction and effective filters, they allow the Coronavirus to infect cells on culture panels, which are cells that swell and become distinctly circular when the virus is transmitted and begins to replicate itself en masse.

The question that Christina Nystrom is looking for an answer to is whether we really have a drug that is ready-made, or perhaps almost ready to treat Corona – the so-called antiviral drug – that can somehow prevent the virus from progressing.

Coronavirus medicine shortage

Today there are few or fewer effective anti-HIV drugs, a few hepatitis viruses and a few types of herpes viruses. But there is a shortage of medicines for more than 95 percent of all viruses that cause disease in humans.

We have broad spectrum antibiotics against bacteria, but almost none against viruses. How is that?

One answer is that bacteria have more common components than viruses. This made it easier to develop large-scale drugs. On the contrary, viruses are very different from each other.

A broad-spectrum antiviral agent can be used as soon as a new virus emerges, just as we use broad-spectrum antibiotics against different types of bacteria.

Break the chains of infection

By using an antiviral drug, you can break the chains of infection, and that’s exactly what nearly everything is about in any pandemic. Mouthguards, restraints, and other measures have a limited effect at best. If we had an anticonvulsant drug against the Coronavirus, we might not have had this epidemic, ”says Niklas Arnberg, professor of virology at Umeå.

A drug for hitherto unknown viruses

Antiviral drugs do not reduce disease and only prevent death. They also prevent the virus from multiplying and thus slow down the spread of infection.

Vaccines are great too, but we cannot develop vaccines against a new virus that we do not know. This time, it takes a year and a half at best to roll out a vaccine for everyone, but if we already had a good antiviral drug against the usual seasonal coronavirus, it would likely have been used since the first day against the new coronavirus, Niklas Arnberg says.

Read more: What is really in the syringe?

Three anti-virus filters

The cells that Christina Nystrom at the rice mill in Gothenburg cause for being infected with the Coronavirus are called Vero cells and come originally from the African Green Market. It has access to an entire library of materials, 1500 molecules, which it systematically tests to see if any of them have an effect against infection.

There are three different interesting chemical structures.

We are now investigating the materials that have proven promising. This means it looks good in Vero cells, and now we want to see if it also works in human cells. What we do know is that the substances prevent infection, so we do not see any new viruses reproducing, and therefore we are not saying that they do not enter cells, but that there is a pause in the system somewhere. What exactly is the mechanism behind us, we are very interested to know. But before we talk more about the topics in question, we really want to check them out so we know how they work.

Read more: Virus Control – More research is needed

Viruses cannot be cultured without the host cells that can infect them, and thus are difficult to study. Here, Vero cells were infected with the Coronavirus from Covid patients. Photo: NIAID, CC BY 2.0

Reuse the medicine

A change of purpose – reorienting a drug or finding a new use for a proven substance – became important during the Corona crisis. But this is not a new phenomenon. Throughout history, drug recycling has introduced many new treatments, not least in the field of cancer. Some examples are aspirin, which is intended to be a pain reliever but has then been shown to be effective in preventing heart disease, sildenafil from Pfizer that treats angina pectoris but – when it didn’t work out well – it was redirected to the potent Viagra and tretinoin which treat both From acne and tretinoin. blood cancer.

Anti-virus hits widely

Anna Lena Spitz is a professor in the Department of Molecular Biological Sciences at the Wiener-Green Institute of the University of Stockholm. It has been working against viruses since HIV destroyed the worst, and is now looking for a treatment to get rid of the coronavirus, but it should hopefully also help fight many other viruses.

Thus it could be an antiviral drug with a broad effect, which is the thing that is missing today.

We have been working with an anti-virus molecule for several years. It turns out that this molecule stops the process that allows some viruses to enter the host cell. Our molecule delays this whole process, and the virus is at least temporarily repelled. She says this was a discovery we made by accident from the start.

A natural anti-virus mechanism

This process is called cell endocytosis, and it means that the virus is surrounded by the affected cell membrane, its shell, which forms a small bubble, and pushes the virus into the cell.

When I read that the Corona virus uses the same method to infect cells, I saw the possibilities, says Anna Lena Spitz.

The molecule researchers are working with is a piece of genetic material – DNA or RNA – which somehow means that the cell membrane cannot form a welcome bubble that attracts infection to the cell.

Coronavirus enters the cell with a bubble

Cell endocytosis is a process in which cells absorb substances from the outside – such as proteins – by coating them with the cell membrane. It occurs completely naturally inside a human cell. Viruses can also use them to enter and infect cells.

Nasal spray against the virus

We don’t know exactly what it looks like, but this indicates that we may have identified a naturally occurring antivirus mechanism – one that we carry. And now we are working on improving it.

Anna Lena Spitz and her colleagues published successful results using this treatment on mice infected with influenza and common cold viruses, known as rs viruses.

The goal is to make an anti-virus nasal spray or inhaler, and among the international staff is a group in Denmark that works with another type of anti-virus molecule and another in Germany that searches for a substance that penetrates the envelope of the virus and causes it to rupture. Just like soap does with the Coronavirus when we wash our hands.

This is how viruses work – unlike bacteria

It is important to distinguish between viruses and bacteria. Both are so small that they are invisible to the naked eye, and many of them cause diseases to both humans and animals, but then the similarities end.

Bacteria are single-celled organisms that have their own genetic material, which can usually reproduce outside of the host organism and in more diverse environments.

Viruses are something between life and the dead. A piece of genetic code, without its own cell and metabolism, but with the ability to reproduce, evolve and spread around the world.

Viruses are about 100 to 1,000 times smaller than bacteria and it took until the 1930s before they were discovered. The common cold virus, for example, is about a thousand times smaller than a normal skin cell.

There are millions of types of viruses and they work in many different ways. But it is mainly about the virus using proteins in its coat to attach to, open, and penetrate the host cell.

Once the virus enters the cell, the virus hijacks the host’s reproductive system for its benefit and begins producing itself in a mass version. Most of the time, the hijacked cell dies, which is blown up by all the virus particles and spreads copies of the virus to other cells, and to another host.

Text: Thomas Lindblad on behalf of forskning.se

“Extreme tv maven. Beer fanatic. Friendly bacon fan. Communicator. Wannabe travel expert.”

More Stories

Why Rare Earth Metals for Electric Cars Are Crucial for Modern Mobility

“We want to promote critical rules approach”

“A lot happened during the trip,” Jönköping County Council