Sometimes it can be difficult to see the simpler solution.

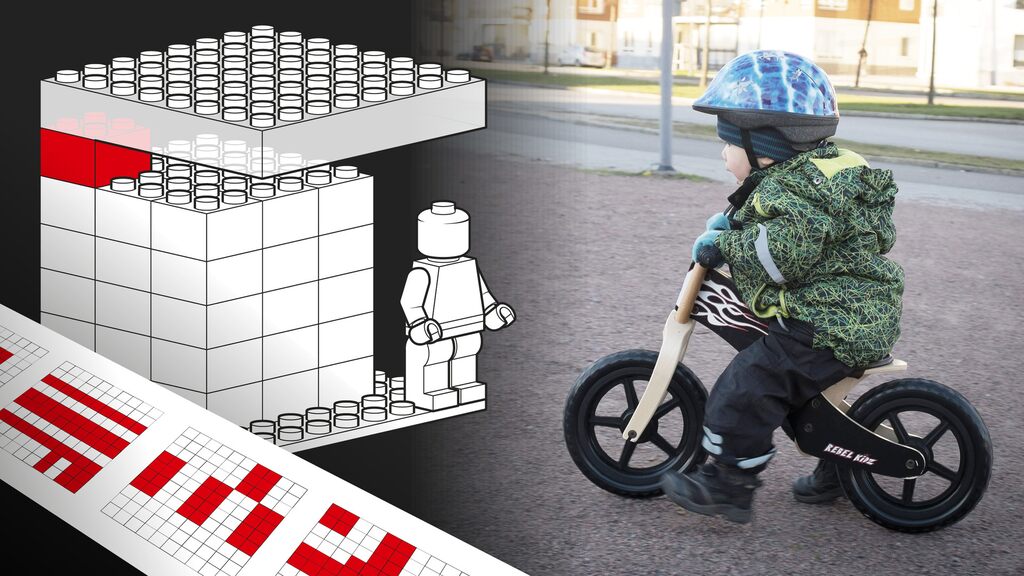

Imagine a contracted tower, with a one-piece roof in one corner. How can you reinforce a building so that it can withstand the weight of the bricks, without the roof collapsing and falling on the poor lego man below?

“You get a dollar if you can handle this. Every extra piece of Lego you add costs a dime. Change the design as you like, and take the time you want,” were the instructions for a group of people who were assigned the task. Although they cost money, most of them put up three more, one on each corner, to keep the ceiling in place.

In another group, where the experimenter added the sentence “But removing the pieces is free and costs nothing” in the instructions, the majority came to the conclusion that the simplest and cheapest solution is of course removing the only piece in the corner, and placing it the ceiling is stored directly below.

– The sentence “But removing the pieces is free” does not contain any new information. It is not necessary. But it makes participants think that it is a possible alternative to removing the bits, says Gabrielle Adams, a social psychology researcher at the University of Virginia in Charlottesville, USA.

As long as we give them the idea that they can remove something, most people like this solution. Therefore, we can conclude that when people in the first case did not remove a piece, it was possible that they did not even consider this possibility, says Benjamin Converse, a researcher in social psychology and cognitive psychology at the same university.

“Perfection does not come true Antoine de Saint-Exupéry, author of The Little Prince, wrote when nothing else could be added, but when nothing else could be removed. Phrases like “less is more” and “kill your dear ones” convey the same thing: that the best solution is often peeling rather than adding.

We start to think about whether these reminders are in place because people otherwise don’t come up with that option. Benjamin Converse says there has been no research on this topic.

The first idea to investigate the matter further came when a colleague of Gabrielle Adams and Benjamin Converse built a bridge in Lego with his son. The bronze poles were of different heights, and while the fellow was looking for another Lego piece to level it, the son solved the problem by removing a piece of the longer leg instead.

We have made more similar observations. When people need to change something, they ask themselves what they can add. But they don’t ask themselves what they can remove, says Gabrielle Adams.

The researchers conducted many systematic studies, asking people to improve things like buildings in Lego, recipes, articles, and itineraries, and they found that the observations were correct. The majority of participants wanted to add more rather than subtract. The only exception was when the recipes contained unnecessary or unexpected ingredients, such as chocolate on hot cheese sandwiches.

Gabrielle Adams and her staff also examined all responses received when the new university president asked staff and students for suggestions for improvements.

Then we saw that even in the real world and with real proposals, people are more likely to come up with ideas for adding new things. Benjamin Converse says they are more attractive.

The next step for researchers To see why we work like this.

We came up with two main alternatives. People may think of the two types of change equally, but they prefer to add on for some reason. Or, they might not even consider the subtraction at all. Benjamin Converse says they’re just looking for things to add without thinking about downsizing.

The last assignment suggests with a node tower that will pass brick and similar tests, as people have to suggest improvements to the miniature golf course or create a symmetrical pattern while solving another task.

When you are trying to improve something, the quick question, “What can I add to this?” It appears in the header by default. Thinking about the subtraction doesn’t have to be more difficult, but it looks like we have to do a lot more to come up with it, says Benjamin Converse.

The researchers’ results were published this week in the journal nature.

There are many real examples On the human tendency to add to the improvement of things when it is better to subtract.

You can compare how Benjamin and I learned to ride a bike to the way our young children are learning to ride a bike now. Benjamin and I rode tricycles and bikes with support wheels. Gabrielle Adams says that most children nowadays are learning to ride motorcycles.

The The first bike was invented in Germany in 1817, and it was just a bicycle. Pedals didn’t get bikes until 50 years later. However, it took until the end of the 1990s for someone to come up with the idea To mass produce kids jogging bikes, And I understood it was better to remove the pedals than to put on the support wheels.

The researchers’ findings may also explain the popularity of cleaning expert Mary Kondo and other advocates of eliminating unnecessary items and living less.

– Mary Kondo reminds people to clean up. This is helpful because our work indicates that people are not spontaneously thinking of it as a vehicle for improvement. There are many books on how to simplify things. The fact that they are so successful and popular indicates that it is a new idea for people. This is in line with our findings, says Gabrielle Adams.

So it’s worth noting that Mary Kondo has now started selling the funds. So you can now buy more boxes from them to save the things you like, says Benjamin Converse.

Researchers say that our tendency to expand rather than shrink has consequences, both for our daily life and for society as a whole.

When it comes to things like climate change, racism and such difficult and dangerous problems, we can ask ourselves what we can do, and what we can remove. Maybe we need to point out that and not just ask how to improve things, but how can we improve things by adding? How can we improve things by removing them? Gabrielle Adams says.

We can see really big problems as the results of all the small evaluations and decisions we make at an individual level. If we miss the small impact of removing something on an individual level, says Benjamin Converse, it can all turn into large-scale problems.

“Unapologetic writer. Bacon enthusiast. Introvert. Evil troublemaker. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

More than 100 Republicans rule: Trump is unfit | World

Summer in P1 with Margrethe Vestager

Huge asteroid approaching Earth | World