Should we let AI drive integration actions?

Matthias Pigmo writes in Aftonbladet (25/5) About the benefits of replacing politicians with artificial intelligence systems. When AI and the US allowed AI to “handle the transfer of newcomers,” it “slightly unexpectedly” led to a “more successful integration.” According to Pigmo, this is because the system is independent of “Twitter mobs and polls”.

At the same time, there is debate about whether the AI tool Chrome – which the Swedish Public Employment Service uses to screen job seekers – really works as it should. at Article in DN (7/5) It seems that many of the Authority’s employees are skeptical about the tool. They believe that “the bot makes wrong decisions that lead to people who need other kinds of help coming to Chrome.”

And recently, I interviewed Liv Sandberg, the new head of the Nordic Chinese app Tiktok i DN (26/5). It describes how Tiktok uses “both artificial intelligence and natural people” to ensure that content “does not violate the app’s regulations.”

In other words. AI discusses It is discussed at many levels of society and regions, but always according to the same premises. Questioning the prevailing understanding of what artificial intelligence is is based on its illogicality. Artificial intelligence, artificial intelligence, artificial and intelligent. According to Matthias Pigmo as well as textbooks in the field, intelligence means rationality and independence.

But the truth is, AI is not particularly artificial, nor is it intelligent at worst. At least that’s what the famous Australian researcher Kate Crawford claims in her book “Atlas of Artificial Intelligence” recently published by Yale University Press.

Kate Crawford has been researching artificial intelligence for over 20 years. Her track record is impressive; In addition to several research positions, she has written for Harper’s Bazaar and the New York Times, and has advised lawmakers at the United Nations and the White House. In The Atlas of Artificial Intelligence, you take a holistic educational approach to the history of AI ideas, political implications and physical foundations.

When companies apply AI to browse job applications, women are screened, and when AI is used in the name of security and surveillance, the result is often racial profiling.

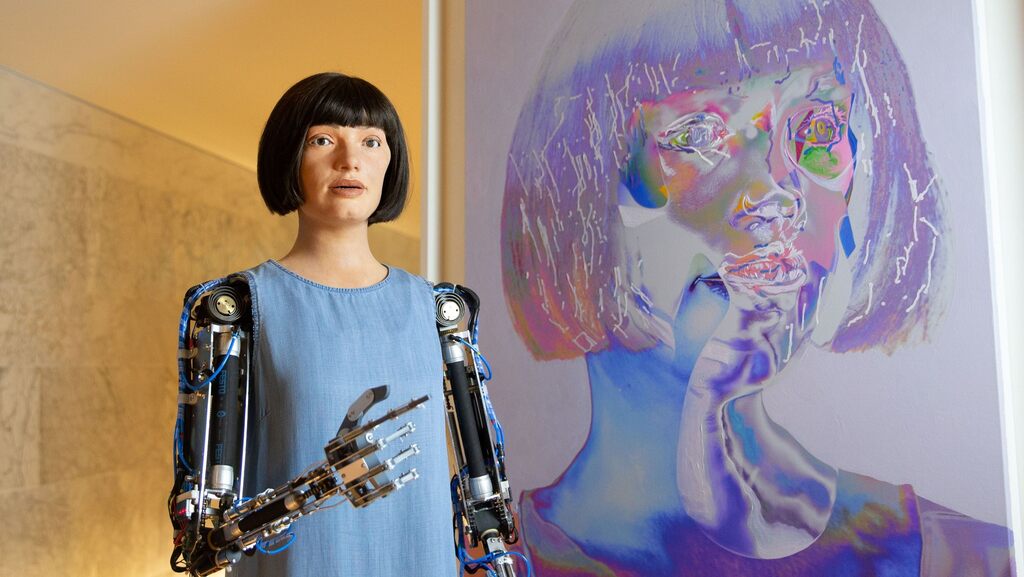

The AI acronym is used for an almost confusing contrast system. As the introductory illustrations show, many people like to use AI as a cue word, without specifying in detail what is actually meant. As Crawford also points out, artificial intelligence is a controversial term in computer science circles, and the word “machine learning” is often used internally instead. The AI label is especially useful when it comes to opinion generation, lobbying, or looking for investors. The very word that AI has in its mystical mystery an atmosphere of a magical future, it alludes to science fiction, gives promises of the future and the endless possibilities of technology. When AI is called upon, we associate it with imagination, with movies like “Her,” “Blade runner” or “Terminator” — which is exactly what the tech moguls wanted.

What is artificial intelligence based Simply to whom to ask. The guy on the street might mention Apple’s Siri, Amazon’s cloud service, Tesla cars, or the Google search algorithm. If you ask deep learning experts, as Kate Crawford writes, they are likely to give an incomprehensible answer about how “neural networks organized in dozens of layers receive the described data, assign them to weight and threshold values, and classify the data in ways that cannot be fully explained.”

Simply put, it can be said that artificial intelligence is a computer system that sorts information in a specific area. An example of this is car photos captured by CCTV, as the system becomes “better” at recognizing cars the more photos are sorted. This particular example is related to the aha moment in the Atlas of Artificial Intelligence. Kate Crawford reports that when we assure Google in good faith that we are “not a bot” to access various websites by clicking on images that represent cars, pedestrian crossings or street lamps, we are doing an unpaid Google AI bot sort. We volunteer to improve technology that can be sold, among other things, to private security companies.

The assumption that intelligence can be created artificially is based on an idea of intelligence that has deep historical ideological roots – an idea that Kate Crawford is highly critical of. MIT professor Marvin Minsky was quoted as saying when asked if machines can think: We can think and we’re like meat machines.”

Android devices do not dream of electronic sheep. There is no straight line between creating an advanced data sorting machine and the subconscious mind

Crawford also takes Even philosophy professor Hubert Dreyfuss, who in the early 1960s lamented that many engineers “do not even think about the possibility of the brain dealing with information in a fundamentally different way than a computer.” Dreyfus later wrote a book called What Computers Can’t Do in which he pointed out that human intelligence depends to a large extent on subconscious and subconscious processes, as opposed to computers which require all information operations to be explicit and formal. The less formal aspects of intelligence must be adapted or canceled to computer conditions, which means that computers deal with information in an essentially human way. Android devices do not dream of electronic sheep. There is no straight line between creating an advanced data sorting machine and the subconscious mind.

Kate Crawford believes that this fallacy is a “genetic sin” that has come to characterize the entire field of research as well as the public’s view of artificial intelligence. She calls it the ideology of Cartesian dualism, in which artificial intelligence is understood as an abstract, disembodied intelligence, apart from any relationship with the physical world. But AI, according to Kate Crawford, is highly “embodied” and relies on “natural resources, fuels, human labour, infrastructure, logistics, history, and classification.”

The Atlas of Artificial Intelligence is moving wide. Crawford takes the reader into the filthy and dangerous mining corridors of Indonesia where the rare minerals that build the machines (computers, cell phones, huge server halls that consume energy and water) are mined and artificial intelligence systems do. It shows with painful clarity how artificial intelligence is not at all artificial but physical, as well as a highly exploitative force.

people rating Based on appearance or other surface features that occur, among other things, in artificial intelligence technology for facial recognition. Kate Crawford reminds us of the biological and ethnological roots of taxonomy. Contrary to what Matthias Pigmo claims, there are many cases where supposed “independence” does not always mean justice. When companies apply AI to browsing job applications, women are screened, and when AI is used in the name of security and surveillance, the result is often racial profiling, and black people are categorized as criminals and terrorists.

The Artificial Intelligence Atlas also deals with how AI technology reclaims and advances decades of labor law regulation. What is described as technology development and automation is really a backlash. Proceeding from the fact that conditions in workplaces in the West are increasingly adapted to human needs, we have again become cogs in the machine, absolutely indispensable assistants to machines.

Regardless of whether we work in warehouses, as a food carrier, with the press or in the Swedish Public Employment Service, we are forced to relate to the data collection that controls and “simplifies” our work. These metrics, for statistics, ignore and report how long it takes to get from restaurant to customer, or to load a package, or in which paragraph the reader is tired of an article and clicking away.

With The Atlas of Artificial Intelligence, Kate Crawford wants us to start talking about AI in a new way: not as something distant, futuristic, and abstract. But as something that is here and now, and that actually shapes our work, our planet, and our lives.

Read more Saga Kavalin texts.

“Entrepreneur. Freelance introvert. Creator. Passionate reader. Certified beer ninja. Food nerd.”

More Stories

Logitech Steering Wheel News: New Steering Wheels, Gear Lever, and Handbrake in Direct Drive Series

Garmin Launches inReach Messenger Plus App

Why Rare Earth Metals for Electric Cars Are Crucial for Modern Mobility