Marcus Gustafsson,

Santa Pistol, Boss Dynamite, Cali Cannon and Tumba Tarzan. Dangerous criminals and league leaders earning titles — or titles — is nothing new. Certainly there are anthropologists who can explain why man has a tendency to give the worst names ever to all criminals, and sometimes those with human souls on their consciences, the nicest names ever.

Part of the explanation may lie in the fact that the story of known criminals, as well as news coverage of them, sometimes balances on the border of being seen as pure fiction. I remember first hand how, as a 22-year-old news reporter at Aftonbladet newspaper, I met Lars Inge “Svarten” Svartenbrandt, for a day-long interview. Svartenbrandt was recently rescued and claimed to have met God while showering in Norrköping prison. He sat and read the Bible to me for hours before the symbolic baptism of the adults took place. Svartenbrandt, one of Sweden’s most notorious criminals, went down to the lake outside Kumla, wearing a white robe, and was then lowered into the water by a priest. The news value of this article can rightfully be questioned, but it was perhaps a kind of cinematic entertainment sequence for me and the readers in Black’s life story. Two years later, Svartenbrandt robbed a post office again.

For the media, there are also practical explanations for why criminals get the nicknames and titles they sometimes do. It is not uncommon for these criminals to be, at least initially, unknown to the media, and sometimes not identified by the police. Of course, they can only be called “perpetrator” or “33-year-old” if the age is known, but for reasons of understanding it is easier and more effective with names like Hagamannen, Lasermanen, or Arbojakvinan. Although these three were later identified and named in the media as Niklas Lindgren, John Ausonius, and Johanna Müller, their given names have become quite impossible to get rid of.

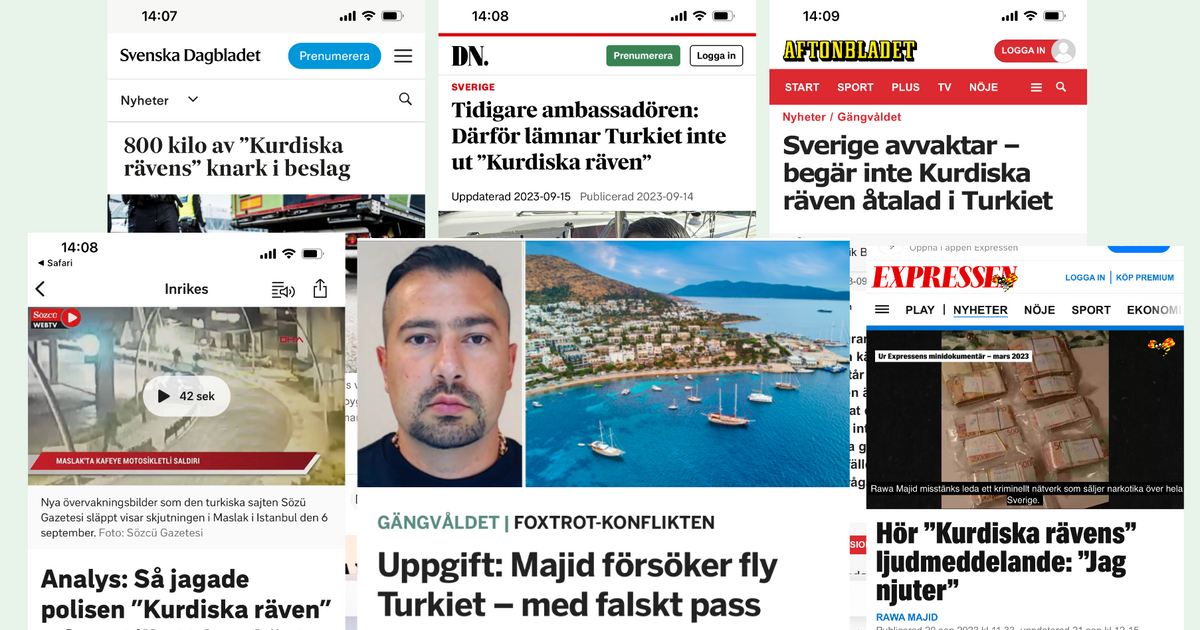

Even the leader of the Foxtrot criminal network, Rua Majeed, now referred to as the “Kurdish Fox”, was initially unknown in the media. He himself called himself “Foxkurdish” on the criminals’ favorite platform, Encrochat. He quickly became the “Kurdish Fox” in the Swedish media, as well as in Omni. By using a nickname, we in the media can tell who the person is talking about, without actually printing their real name. It was the same with his guerrilla enemy, Mikael Tinzos, the leader of the Dalennävterket, which at the same time began to be rewritten under the name “The Greek”. In the ongoing internal settlement within the Foxtrot network, we have recently become familiar with the nickname “Strawberry Man,” as Roy Majed’s former friend Ismail Abdo is called in the media.

In principle, I do not like to use titles and titles. It can contribute to downplaying atrocity crimes, and we risk losing cases of dangerous criminals. Therefore, we at Omni have been discussing for some time now to stop writing “Kurdish Fox”, “Greek”, and “Strawberry”. We concluded that we should be very frugal in use, even if we do not impose a complete ban. We said that it is best to use real names in titles and in running text, although we may sometimes have to include “who also became known as the Kurdish Crow,” to increase understanding for readers. It’s a bit like when we write about Platform , formerly known as Twitter.

But this week I heard from Barzan Kokaya, head of the Kurdish Patriotic Union. Now he presented another angle on this issue. Specifically, how many Kurds in Sweden feel uncomfortable about the way the name “Kurdish Fox” is used in the media. In the same way that the Chinese suffered from the name China Virus, before the media changed the line. I called and spoke with Barzan earlier today, and he certainly has a very strong point. He describes how many Kurds in Sweden suffer from the media’s use of this name, and tells us how vulnerable young Kurds feel in schoolyards. Of course, it doesn’t have to be this way.

As of today, we at Omni have decided to be very restrictive when we refer to the leader of the Foxtrot criminal network, Rua Majid, by his nickname. There were good reasons to stop using the name earlier, but the Swedish Kurds’ reaction to the name was the straw that broke the camel’s back. There may, for the sake of understanding, be a reason to make an exception at some point and mention the noun in a subordinate clause or so. But in other aspects, we clean up the title. We also access and edit our most recently published articles.

/ Marcus

“Unapologetic writer. Bacon enthusiast. Introvert. Evil troublemaker. Friend of animals everywhere.”

More Stories

More than 100 Republicans rule: Trump is unfit | World

Summer in P1 with Margrethe Vestager

Huge asteroid approaching Earth | World