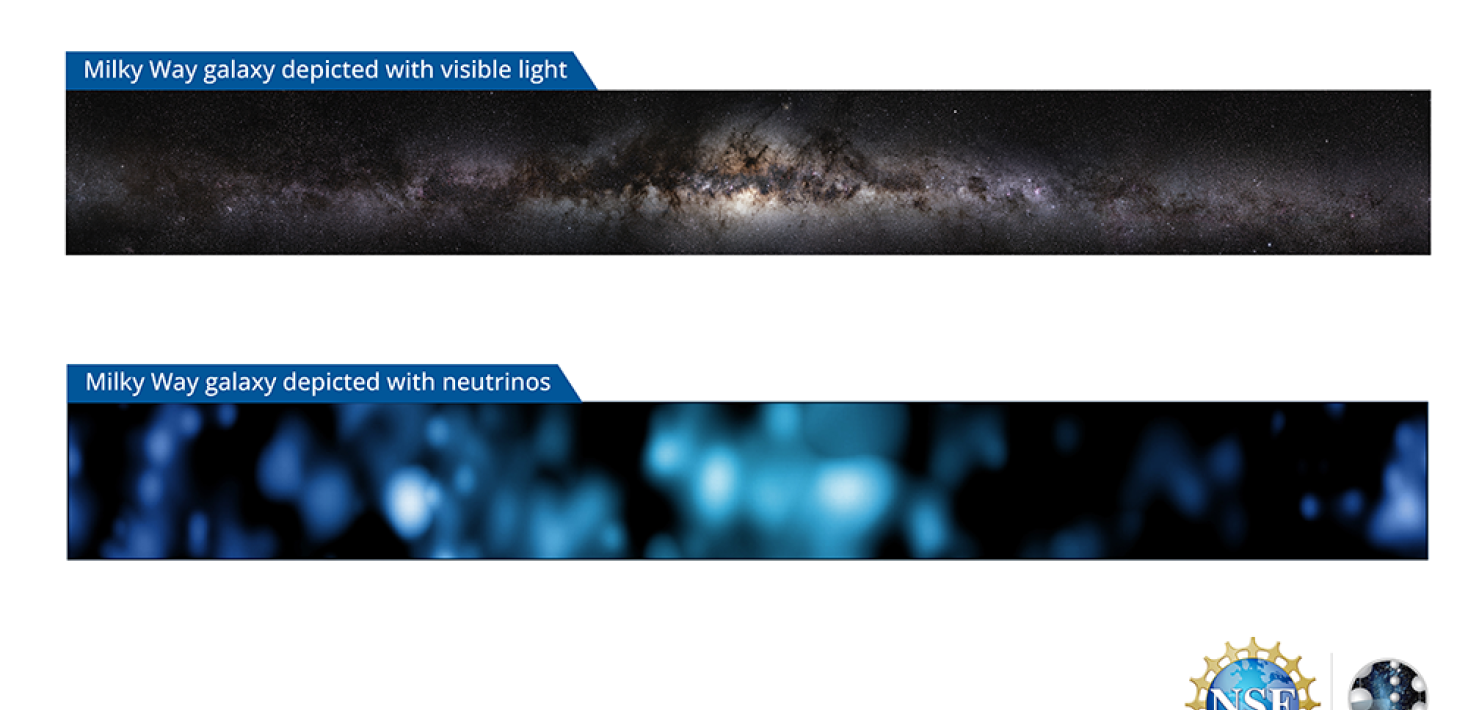

For the first time, scientists have produced an image of the Milky Way using neutrinos, which were observed using the IceCube telescope in the Antarctic ice. The image indicates that more cosmic rays are hitting gas and dust in the central parts of the Milky Way than previously thought. The results are published in the journal Science.

IceCube at the South Pole with the Milky Way in the background. Photo: Martin Wolf

Throughout history, the spectacle of the Milky Way has inspired awe, which can be seen with the naked eye as a hazy band of stars stretching across the sky. Now researchers under the international collaboration IceCube have produced an image of the Milky Way with the help of neutrinos – tiny, ghost-like particles that fly freely through matter and space.

Neutrino telescope in Antarctic ice

The neutrinos were recorded using the IceCube Neutrino Observatory, a neutrino telescope built into Antarctic ice that monitors a billion tons of Antarctic glaciers for rare neutrino collisions. Researchers at Stockholm and Uppsala Universities have been involved with the IceCube for a long time and have been involved in the analysis of data collected during ten years of observations and in the interpretation of the results.

Chad Finley.

Photo: Soren Anderson

Seeing our galaxy with the help of neutrinos is something we dreamed of, but seemed too far-fetched for our project for many years to come. What has now made this result possible is the revolution in machine learning, which has allowed us to explore our data more thoroughly than we’ve ever been able to do before, says Chad Finlay, an assistant professor in Stockholm University’s Department of Physics and one of the IceCube researchers who worked on the study.

Neutrino Prediction Challenge

In the last century, astronomers began to study the Milky Way in all wavelengths of light, from radio waves to gamma rays. High-energy gamma rays in our galaxy are thought to originate primarily when cosmic rays, high-energy protons, and atomic nuclei collide with galactic gas and dust. This process will also produce neutrinos. But high uncertainties about the occurrence of these collisions in different parts of our galaxy have made neutrino predictions a challenge.

The analysis method that was used to obtain the latest results was originally developed at Stockholm University in 2017 by Jonathan Domm, a postdoctoral fellow at the Oskar Klein Centre.

“He realized that if the higher range of these neutrino predictions were correct, it was almost possible to detect events in the IceCube data that we had at the time,” says Chad Finley.

AI help

The Milky Way is imaged with visible light and neutrinos. Photo: IceCube/NSF

However, the researchers believed that many more years of data collection would be needed to truly map neutrino lines in the Milky Way. The IceCube telescope records billions of events each year, but only a very small fraction can be associated with neutrinos from space – one in every hundred million recorded events. Determining these neutrino events is a difficult task, but using artificial intelligence (so-called deep neural networks) they have been able to do it 20 times more efficiently than before.

High-energy neutrinos give us a great new tool for studying the Milky Way. The next step is to identify neutrino sources, which are likely sites of accelerating galactic cosmic rays to high energies, says Olga Buettner, professor of physics at Uppsala University.

– Previous discoveries with IceCube were of neutrino radiation from much greater distances and it’s really exciting that we can now discern a neutrino image of our galaxy. It opens the way to study additional processes using neutrinos. First of all, it is important to try to identify objects in the Milky Way as sources of neutrinos. IceCube-Gen2, an IceCube upgrade we’re planning now, says Klas Hultqvist, a professor at Stockholm University, will give us much greater sensitivity for further studies of events in the galaxy.

The article “Observation of high-energy neutrinos from the surface of the galaxy” was published in it Science magazine.

Facts about IceCube

The IceCube Collaboration consists of approximately 350 researchers at 58 institutions around the world. Stockholm University and Uppsala University are two of the universities that co-founded IceCube. The IceCube Neutrino Observatory is supported by the US National Science Foundation, as well as the Swedish Research Council and national funders in other member countries.

Read more about IceCube

Last updated: June 30, 2023

Site Manager: Communications Department

“Entrepreneur. Freelance introvert. Creator. Passionate reader. Certified beer ninja. Food nerd.”

More Stories

Logitech Steering Wheel News: New Steering Wheels, Gear Lever, and Handbrake in Direct Drive Series

Garmin Launches inReach Messenger Plus App

Why Rare Earth Metals for Electric Cars Are Crucial for Modern Mobility