But the difference is much smaller than we thought. We can see that it is not a direct ancestor of those of us who live in Europe today, but it is a precedent for hunter-gatherer groups that lived in Europe until the end of the Ice Age, says Matthias Jacobson, professor in the department of organic biology at Uppsala University.

There are very few complete genetic predispositions – through – that are more than 30,000 years old and have been orchestrated. When the research team can now read the entire genome of Peştera Muierii 1, they can see similarities to what people have today in Europe, but they can also see that they are not our ancestors.

Peştera Muierii – one of the three in the Cave of Women

Peştera Muierii 1 is called one of the three individuals whose remains were found in the cave of the same name. Peştera Muierii Cave (Cave of the Hungarian Woman) is the name of a cave system in Baia de Vier in southern Romania. The cave system is known for the remains of cave bears and because skulls and other parts were found in the 1950s by three different women who lived there about 35,000-40,000 years ago.

Other researchers have seen in previous studies that the shape of her skull has similarities to both modern humans and Neanderthals. Therefore, it is assumed that they were more genetically similar to Neanderthals than other contemporary individuals, and in this way stood out from the norm. However, the genetic analysis in the current study shows that it had the same low level of Neanderthal DNA as most remains of other individuals who lived at the same time.

Compared to the remains of some individuals who lived 5,000 years ago, such as Peştera Oase 1, it had half the number of Neanderthal genes.

Genetic bottleneck

An important period in human history is when modern humans spread and begin to emerge from Africa around 80,000 years ago, which is usually described as a genetic bottleneck. The population migrated from the African continent to Asia and Europe. We are still seeing the effects of the relocation today. The genetic variation is less in the population outside Africa than in the population in Africa. The fact that Peştera Muierii 1 has high genetic diversity indicates that the greatest loss of genetic diversity occurs during the last Ice Age (which ended around 10,000 BC) and not during migration out of Africa.

This is interesting because it teaches us more about the early population history of Europe. Peştera Muierii 1 has much more genetic diversity than was thought in Europe at this time. This demonstrates that genetic variation outside of Africa was significant until the last Ice Age, and that it is the Ice Age that is leading to reduced variation in people outside of Africa, says Matthias Jacobson.

Reduced genetic diversity

The researchers were also able to follow genetic variation in Europe over the past 35,000 years, and observed a clear decrease in variance during the last Ice Age. Decreased genetic diversity has been previously linked to the fact that harmful genetic variants are more common in populations outside of Africa, but this has been a controversial issue.

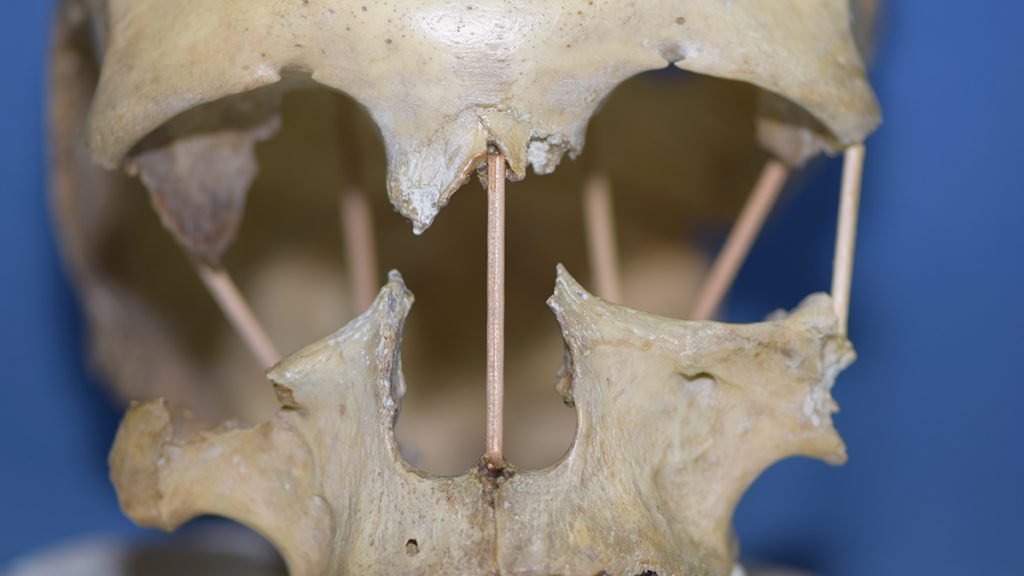

Skull sampling of Peştera Muierii 1. Photo: Matthias Jacobson

Thanks to the fact that we have advanced medical genomics tools, we were able to examine these remains that date back thousands of years and were also able to search for genetic diseases in them. To our surprise, we did not find any differences over the past 35,000 years, despite the fact that some individuals who lived during the Ice Age had low genetic diversity, says Matthias Jacobson.

Now we have everything based on the remains that are present. Peştera Muierii 1 is a culturally and historically significant discovery and is still certainly interesting to researchers in other fields, but from a genetic perspective, all data is now available, says Matthias Jacobson.

Scientific material:

Peştera Muierii skull genome shows high diversity and low mutational load in pre-Ice Age Europe (Svensson E. et al) Current biology

Contact:

Matthias Jacobson, Professor, Department of Biology at Uppsala University, [email protected]

“Extreme tv maven. Beer fanatic. Friendly bacon fan. Communicator. Wannabe travel expert.”

More Stories

Why Rare Earth Metals for Electric Cars Are Crucial for Modern Mobility

“We want to promote critical rules approach”

“A lot happened during the trip,” Jönköping County Council